When my mother read Medea’s Curse—after telling me she enjoyed the story—not being one to gloss over issues, she told me it had two problems:

- “Is the sex really necessary?’ Actually there isn’t much, it’s quite main stream and yes, it is part of the story and character.

And

- “Did you have to give the heroine (Natalie King) bipolar disorder”?

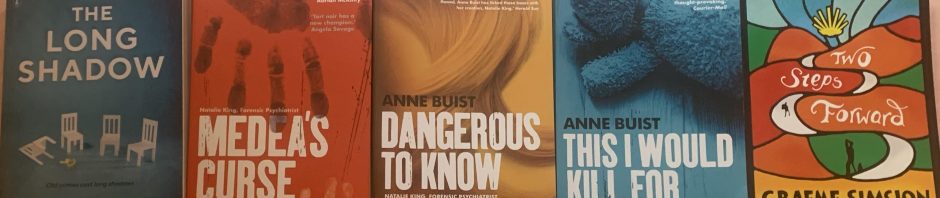

I’ve been thinking quite a lot about this last point. Of course, as the author, I could have “given” her anything (or not). It is common in crime fiction, particularly in a series (the next of mine, Dangerous to Know, is due out in April next year), for the main character to have a vulnerability – often alcoholism and/or depression (even Superman has kryptonite…). It makes them human, accessible, more realistic, and opens options in plots. Natalie, who had a serious motorbike accident at 16 (she was a passenger) and spent a year in rehab, was going originally to be an amputee as a result of this accident. Trouble was, I didn’t know anything about being an amputee. I understand from a colleague (and indeed can imagine) it is a very difficult adjustment; we have wonderful examples who have transcended this (and some who did in sport but not in their life—Oscar Pistorius), including a friend of my daughter’s, who is a Para-Olympian. But to be authentic I would have had to have worked with someone who had been through this and spent a lot of time getting it right.

Why not “give” Natalie something I knew something about—not just because I am a psychiatrist, but because working in perinatal psychiatry I see a lot of women with bipolar who are at a high risk of relapse postnatally? And not just because I know about it, but perhaps also because of my mother’s question. Anyone can get a mental illness. Anyone. Could Natalie having bipolar disorder, just as Carrie does in Homeland help to de-stigmatise the disorder (I didn’t see Homeland until after I’d written the second in the series, Dangerous to Know; I think the writers and actor does a great job though I am frustrated with her at times—as people will be more than likely, with Natalie)?

This is a big ask. Because if she is authentic—including vulnerable and human—she is not going to be perfect. And thus not the poster girl for my profession.

Jacqueline Hopson wrote an article (available online here) in The Psychiatric Bulletin late last year, called “Demonisation of Psychiatrists in Fiction (and why real psychiatrists might want to do something about it)”. I had a registrar a number of years ago look at female psychiatrists in film and they come to similar conclusions (though my registrar added to the list of incompetent, evil and boundary transgressions an alarming rate of female psychiatrists sleeping with their patients—the worst a truly horrible depiction of the love sick doctor running in the rain after Richard Gere—where as in real life, when it does happen (that is love sick or other reasons for transgressions, not running in the rain)—it is 9 to 1 male psychiatrists).

Hopson writes about the “damaging negative, widespread representation that dominates the way psychiatrists are seen”. Think Hannibal Lecter. She gives examples of the evil and pathetic, and comments that part of the background for this is where my profession has come from and not completely emerged: a profession where diagnosis is subjective and there is no “urine test for schizophrenia” and where we have the power (very limited in modern times) to “lock” people up. The debate around categories in DSM (and having ever had homosexuality as a diagnosis) don’t help. Asperger’s in now part of Autism Spectrum—Don Tilman (The Rosie Project/Effect)—might argue “aren’t we all” (on the spectrum)? What is a “disorder”—and how and who should decide?

In addition, psychiatry had a lot of horrible treatments—such as insulin coma and deep sleep therapies—read Frances Farmer’s autobiography Will There Really be a Morning. Others like ECT, which can be life-saving, but was hardly depicted as such in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. If this is representative of how psychiatrists are presented, then I agree with Hobson. Continuing these depictions risks reinforcing negative stereotypes.

But there is another angle. Are we being too precious? A social worker complained about Lydia, a character in The Rosie Project; I don’t see Lydia as representing the profession, though I have met social workers (and other health workers) like her—and she is well meaning and her issue with Don, the hero, is resolved in the end. Perhaps we as psychiatrists are being also being oversensitive, probably because we have been considered within our own profession of medicine, at least until we began getting excited about neurotransmitters and neuroimaging, to be less scientific. Jeffrey Lieberman in Shrinks, blames this on Freud (father of 20th century psychiatry, with a dazzlingly new concept that has changed virtually every person in the Western world’s view of the mind)—Freud started as a neurologist and was keen on evidence based work—but then went into defensiveness in his altercation with Jung (who is the father of psychology).

Novels include some very serious explorations of mental illness; I Know This Much is True, I Never Promised you a Rose Garden and Yalom’s books, himself a psychiatrist, which present historical takes of psychiatrists and philosopher’s and it would be hard to take issue at his characters. Then there are recent thrillers Girl on a Train, Nicci French’s Monday- Friday series; not so positive though in the latter she is the protagonist. In Stieg Larsson’s trilogy the psychiatrist is a rapist psychopath. Crime books by Jonathan Kellerman and Stephen White have a psychotherapist-psychologist hero who is the good guy.

Wiki lists 91 fictional psychiatrists. Of the list of the 10 we most love to watch and the 10 worst psychotherapists on google (note that psychiatrists frequently getting mixed with psychologists and psychotherapists—the latter may or may not be a psychiatrist, and for readers who want the quick explanation, all psychiatrists can prescribe as they are doctors, but not all do psychotherapy), there are only two overlaps—Ben Harmon (American Horror Story episode one) and Hannibal Lecter (Silence of the Lambs). Of the four we love to watch, three are comedies and I don’t think anyone comedies are serious representations, and Ben Sobel (Analyze This) isn’t all bad. Who wouldn’t be anxious seeing a major crime boss? Three of the others are positive depictions—highlighted in Robin Williams portrayal of Sean Maguire in Good Will Hunting. The one I love to watch, Paul Weston (Gabriel Byrne) in In Treatment, though he almost does the dreaded fall in love with a patient, he is mostly a brilliant psychotherapist—I believe some of his sessions are used to train psychoanalysts it is that good. Maybe showing someone good struggling will help “good” psychiatrists who are tempted, not to.

It’s true the bad are really bad. Batman (Harley Quinn who falls in love with Joker, Hugo Strange and Dr Carne- Scarecrow) accounts for three of them and there is another cartoon series also with an evil psychiatrist, a horror series, book-movies eg where Lecter eats his patients (no one surely takes this as representative?). Generally they kill, are unsympathetic or are pathetic—but they are also very, very clearly fiction. They aren’t great images of psychiatrists, who in real life deal with troubled people and carry often a large burden of other people’s pain, and all too often, guilt when they suicide. I Never Promised You a Rose Garden does a much better representation of truth—are people not smart enough to see this is more “real” than Batman?

There is another point. Try googling “fictional neurologists”. You get “do you mean functional”?

“Fictional nurses” gets 117. Of the favorite seven, two are comedy and mostly positive, and only one of the seven gets a mention at the end that the board decrees them as unethical (Nurse Jackie who is addicted to drugs).

So psychiatrists seem to be overrepresented and at least in comparison to nurses more negatively portrayed. Is this better than being too boring to be there at all (neurologists)? Particularly as there is no evidence that this exposure has in anyway helped people understand the difference between types of health professionals in the field (though this, I suspect, is probably is only an issue to those in it)? Are we just being a bit precious? Surely exposure helps de-stigmatisation? And outrageous depictions will be recognised as such? It is going to be hard to avoid these—psychiatry fascinates people, and in order to make fiction entertaining, it’s more than psychiatrists that are portrayed as bad and mad.

Which brings us back to Natalie King; a forensic psychiatrist with bipolar disorder. I know doctors, psychiatrists and lawyers with this disorder. Kay Redfield Jamison, a Professor of Psychiatry (confusing trained in psychology) writes a brilliant account of her own battle with the disorder in An Unquiet Mind. So yes, it is feasible. “Why does she have to play with her medications?” complained my mother. Because doctors think they know better (emotionally, not intellectually), but much more, because (and Jamison talks about this), people with bipolar live for the high. In the early phases of their illness, the dullness of feeling normal is soul destroying for the creative, unbearable for the young, and something some people with bipolar disorder never resolve. Jamison does—so will Natalie, but not in Medea’s Curse. I have the second out next year, the third in first draft form and the fourth (and maybe final) in my head around her arc. She isn’t perfect—and she makes unethical decisions based on her passion for her patients. The not perfect—because I am endeavouring to be real and real people make mistakes, and because I want people to be interested and want to keep reading. The unethical? Because how else to get people to think about these things? There was a TV series called Halifax about a forensic psychiatrist who I think slept with her patients or at least their relatives (as did Susan Lowenstein in Prince of Tides). Most people get sleeping with your patient is wrong (but they would be hard pushed to say why, if it was a country GP who had seen the person once three years earlier for a cold), but few see why relatives might be an issue. Natalie, incidentally, does not, and will not, sleep with her patients—but there are other ethical issues and more and more, these I think need real psychiatrists, to discuss. Natalie King is probably not what Hobson had in mind when she challenged real psychiatrists to do something about the negative stereotypes—but then she isn’t a novelist (or screenwriter), who has different pressures and rules applying. I am not into serial killers and evil psychopaths who act without cause other than to be evil, so I won’t portray psychiatrists like this—but my characters of whatever profession (or unemployed—the job is after all only one aspect of people) do need to be authentic and create conflict. I’ll trust my readers to tell the difference between Dr King and Dr Lecter.

Hi Anne I @AnnieOdyne landed here via Twitter. above, your mention of fictional psychiatrists has made me think of the wonderful and hilarious film <a href="http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0103241/"'What About Bob?' where the therapist is driven crazy and has his life ruined by the patient. If you haven’t seen it, it is family friendly and a joy.

LikeLike

Must look out for it!

LikeLike