As far as I know, Yalom at 83 is still alive and at least until a few years ago, still seeing patients. So writing legacy aside, he stands as a formidable role model of how to grow old actively. I have a friend whose father is about to turn 100 and walks daily and reads: like Yalom, he has also grown old with an active mind.

When I started training in psychiatry in early 80’s Australia the era of group and family therapy was waning but I caught the tail end of it and was lucky enough to have training in both aspects. As well, we had a psychoanalytic psychotherapist come to talk with us first years, an hour I never missed: it is possible I was the only enthusiastic one amongst my cohort as I recall probably talking a good deal more than the others. Subsequently I had my compulsory case supervision of 50 sessions (though that patient still sees or rings me once a year, some nearly 30 years later), and had another three years supervision while I decided if this was what I wanted to specialise in. In the end, academe pulled me away from becoming a psychotherapist, but I have always had a fondness for what first drove me to do psychiatry—a curiosity about the human condition.

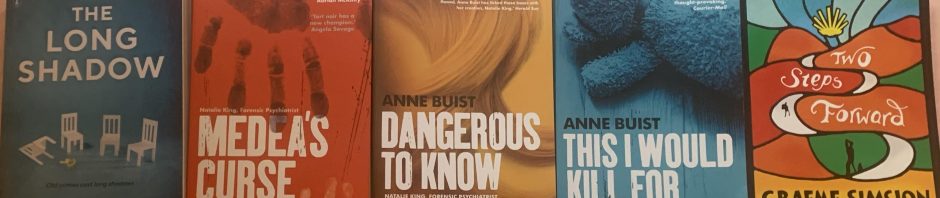

It is popular wisdom that people go into psychiatry (and psychology) looking for answers to their own problems. Either that, or psychiatry causes them to become troubled. This was raised with me last week in a radio interview: why did I make the protagonist of Medea’s Curse, Natalie King, flawed, and indeed with bipolar disorder? Aside from the obvious answer, that this is what I know well, people are not interested and engaged with “perfect” one dimensional (and unreal) characters, and mental illness needs to be destigmatised – as they are common, all sorts of people, including psychiatrists (who arguably are in a better position to understand and manage them) will suffer from them.

I think there is some truth to helping people attracts those who wish to understand (in Natalie’s case she developed bipolar in her intern year, so already a doctor, psychiatry was an obvious choice) and that the profession provides trauma which can cause problems—but historically, sadly less so now, we were encouraged to have our own therapy to help deal with either what drove us and may still trouble us, and how working with those with mental illnesses can be difficult. To be a good therapist, even one who works more in a supportive manner, it is critical to understand what is happening in the process—as well as to question what it is in the therapeutic relationship that can help you understand who your patient is.

At times, what we see is disturbing. I have worked on forensic cases where the death or abuse of a child at the hands of their parent, which has been traumatic for all concerned. In Spinelli’s book on Infanticide, one therapist relates how she struggled to do therapy with a woman who had killed her child—yet in doing so, as those in helping professions must, she learned empathy and saw a bigger picture than the narrow one suggested by media headings like ‘Child Murderer’. Above all, to prevent and to aid recovery, we must understand.

Yalom, a Professor of Psychiatry at Stanford, with a long history of writing non-fiction and fiction with a psychological and philosophical bent (eg a fictitious account of Breuer meeting Nietszche in When Nietszche Wept), is a psychotherapist and strongly advocates for new therapists to experience their own therapy in one form or another. In The Gift of Therapy he shares with startling honesty how it has felt for him from the many years sitting in the chair, as well as on the couch with a series of therapists. He calls himself an Existential Therapist (and his written on this too) and his therapy is the style I have over years practised—albeit perhaps not as well! It is a therapy that keeps in the patient’s present dilemma, but using Freudian theory of transference and countertransference to help patients have an emotional experience in order to bring about change. No one has ever truly changed, just because they were told to—they have to want to, and feel why and how.

For non-therapists with an interest in the process, Love’s Executioner is a wonderful collection of his cases, starting with why he doesn’t do therapy with people in love (he hates to disillusion them with reality) even though he then does—with a 70 year old! That this is a case who he thought he failed with but then as part of a pre-post therapy study turns out to be his biggest success, it shows much of the complexity and wonder of therapy. To say nothing of some of the problems of researching this area. In another of his books, he and his patient write about what helped after each session—there was little overlap. In Love’s Executioner there are plenty of other stories too—all compelling and fascinating enough to make me wonder at my decision to be more eclectic and not spend more time helping people make sense of their worlds.

In what may be his last book, Staring into the Sun, his treatise is about death—and our fear of it. He uses anecdotes from his many years as a therapist, as well as his own experience of facing mortality. His writing is easily accessible, thoughtful, and what is most surprising—though this may just be me and because I am getting older—is his relative humbleness and willingness to admit to his own anxieties and failings (but not rest assured in a neurotic Woody Allen manner). He raises, as did Carl Rodgers many years earlier, the prospect of caring for a patient—really caring, and that this is the key to real success in therapy rather than “technique”. With this comes the tricky aspect of self-disclosure by the therapist (frowned on by many) and how critical this is to successful therapy. Here I think Yalom makes it clear that self-disclosure is not about chatting with your patient about your sex life or how you hate your mother, but a sharing of feelings (generally countertransference, is the feelings the patient evokes in you), to make you human—and show how the patient can touch you. With now 25 years experience, I applaud his honesty, and can say without doubt that those patients I have had the most success with are the ones where we have managed to “click” –and that I have been able to show I really do care. For many patients this is, sadly, a novel experience.

For the handful of patients I have seen long term, it has been an honour to share their lives and struggles and ultimate triumphs, and help in whatever way I could. They surely taught me as much as I helped them—and while Yalom might indeed have a degree of narcissicism (almost synonymous with “Professor”) he is insightful and intelligent and it is hard not to forgive him much because of this—and the wonderful works he has left for many generations of therapists to learn from.

I very much enjoyed reading this! Years ago, I came across Love’s Executioner in a bag of give-away books a friend had left at my house. I was riveted. It was right on time. It opened my eyes and gave me words to describe some ideas which had been trying to form. A few years later I returned to school to study counseling. Yalom has had a big impact.

LikeLike

He’s very good at putting psychological ideas into understandable language! Try Momma and the Meaning of Life if you haven’t!

LikeLike

Own it! Own a few others and his group therapy text, and I’ve read a few others. Will have to read his latest next. Love the guy!

LikeLike

Did Yalom see long term clients? You mentioned you had only a handful of them and I wonder about him as most case studies were of limited time therapy.

LikeLike

Hi Renata

my impression was he took them on (at least when he was younger) for at least a few years but I might be wrong! 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike